Do Androids Dream of Joseph Beuys?

In which I write about the genius of Philip K Dick and about Stuka pilots for peace

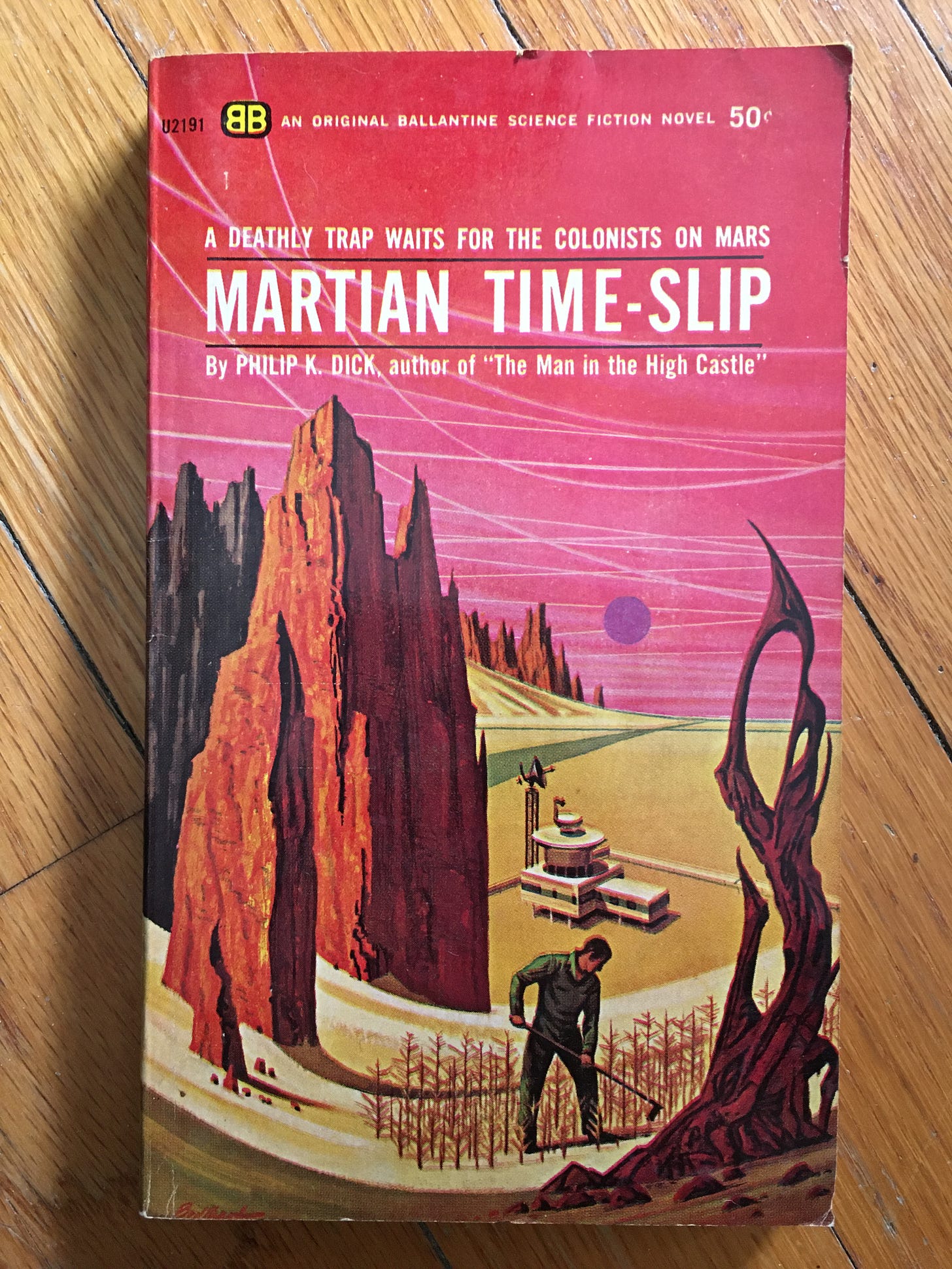

Most people only have second-hand knowledge of some of the most interesting literature ever written: science-fiction novels by Stanisław Lem and Philip K. Dick. Very good movies have been made out of a couple of their books: Blade Runner, Solaris (the Tarkovsky version). Don’t get me wrong: I really like those movies. But as was probably unavoidable, both movies change the book’s stories considerably, leaving out a lot of very important details.

Solaris (the book) actually is a deeply philosophical book about what it might mean to try to establish communication with an alien entity. The film is amazing for all the right reasons. But so is the book — and the reasons are very different. It’s an incredible book (just don’t expect to find a love story in it).

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the book behind Blade Runner) is closer to its movie adaptation than Solaris. Still, there are many details that are missing, details that I find quite crucial. For a lack of a better term I’d call the movie a form of techno noir: it’s almost but not quite as if the source book had been written by Raymond Chandler.

Chandler and Dick were incredible writers — for mutually exclusive reasons. Chandler focused on the hard-boiled detective, who’d go through the world in a completely detached fashion (the writing is very elegant). Dick, in contrast, always focused on the at least somewhat hapless everyday man who somehow finds himself in crazy circumstances (the writing is anything but elegant).

As much as I enjoy reading Chandler, if I had to choose, I’d pick a Dick novel. The reason is simple: even though ostensibly they’re science fiction, they actual deal with the kind of stuff we all have to live with every day: the consequences of a technological world, where the technology was created by people who don’t quite care enough. Sounds familiar?

Here’s an example. In Ubik, main character Joe Chip is perpetually broke (people just barely getting by in their shitty jobs is a theme in Dick’s books). At some stage, he comes back home, and he finds he can’t get in because the door of the apartment (“conapt”) he rents is coin operated. But not only that, the door also features some artificial intelligence which allows it to talk to Chip. Here’s the scene:

“The door refused to open. It said, “Five cents, please.”

He searched his pockets. No more coins; nothing. “I’ll pay you tomorrow,” he told the door. Again he tried the knob. Again it remained locked tight. “What I pay you,” he informed it, “is in the nature of a gratuity; I don’t have to pay you.”

“I think otherwise,” the door said. “Look in the purchase contract you signed when you bought this conapt.”

In his desk drawer he found the contract; since signing it he had found it necessary to refer to the document many times. Sure enough; payment to his door for opening and shutting constituted a mandatory fee. Not a tip.

“You discover I’m right,” the door said. It sounded smug.

From the drawer beside the sink Joe Chip got a stainless steel knife; with it he began systematically to unscrew the bolt assembly of his apt’s money-gulping door.

“I’ll sue you,” the door said as the first screw fell out.

Joe Chip said, “I’ve never been sued by a door. But I guess I can live through it.”

This basic idea runs through most of Dick’s book: instead of focusing on the future as this glorious time where technology solves all the problems, Dick looks at the possible consequences in daily life.

In some ways, the idea of arguing with a door is completely silly. But it’s really not that many steps away from what we already have to go through in daily life. The consequences can be quite grim: I’ve seen more than one report on the news where there were people featured who help older people navigate through overly complicated websites so that they can set up an appointment to get the Covid vaccine.

Here’s a more benign example: the website of US airline United always asks me to enter my first name as listed in my passport (it’s “Jörg”). But an umlaut is not an accepted character! Now, if I enter “Jorg” or “Joerg” and then attempt to scan my passport, it won’t work. I even emailed them and told them about the problem. They said they’d fix it (they didn’t).

However much I enjoy Philip K Dick’s books for the grander ideas explored, it’s the smaller details that really make the work. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? starts out talking about how people really want pets. But since most animals have died out, they now have to accept having android pets. There’s a rumour, though, that there still are some real animals somewhere… This operates on the most basic level of human beings: the need for companionship, for solace provided by a pet (if you live with a cat, dog, or other animal(s) you know what I mean).

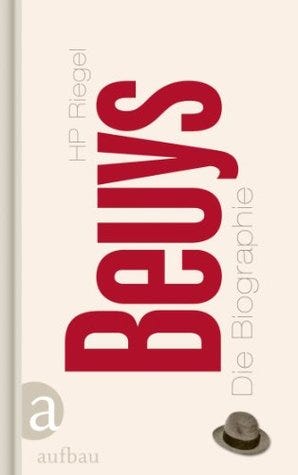

I don’t think I could ever loose pretty much all respect for an artist as quickly as when I read Hans Peter Riegel’s biography of Joseph Beuys (as far as I can tell it’s only available in German). I’m only about one third into the book, and there’s literally no respect left. I had always been a bit ambivalent about Beuys — much that had been constructed about and/or around him reeked of, well, bullshit. But then isn’t that part of the business of art, to create a story around yourself?

Still, to have Riegel systematically deflate or destroy pretty much everything — that was something else. Like I said, I’m only one third into the book, which means I’ve made my way up until his first Fluxus performances (which, Riegel details, were essentially Beuys piggybacking off Nam June Paik and using Fluxus events for his own purposes that were actually completely at odds with Fluxus ideas). Everything I had heard about Beuys that dealt with the time before turned out to be either hearsay or outright false.

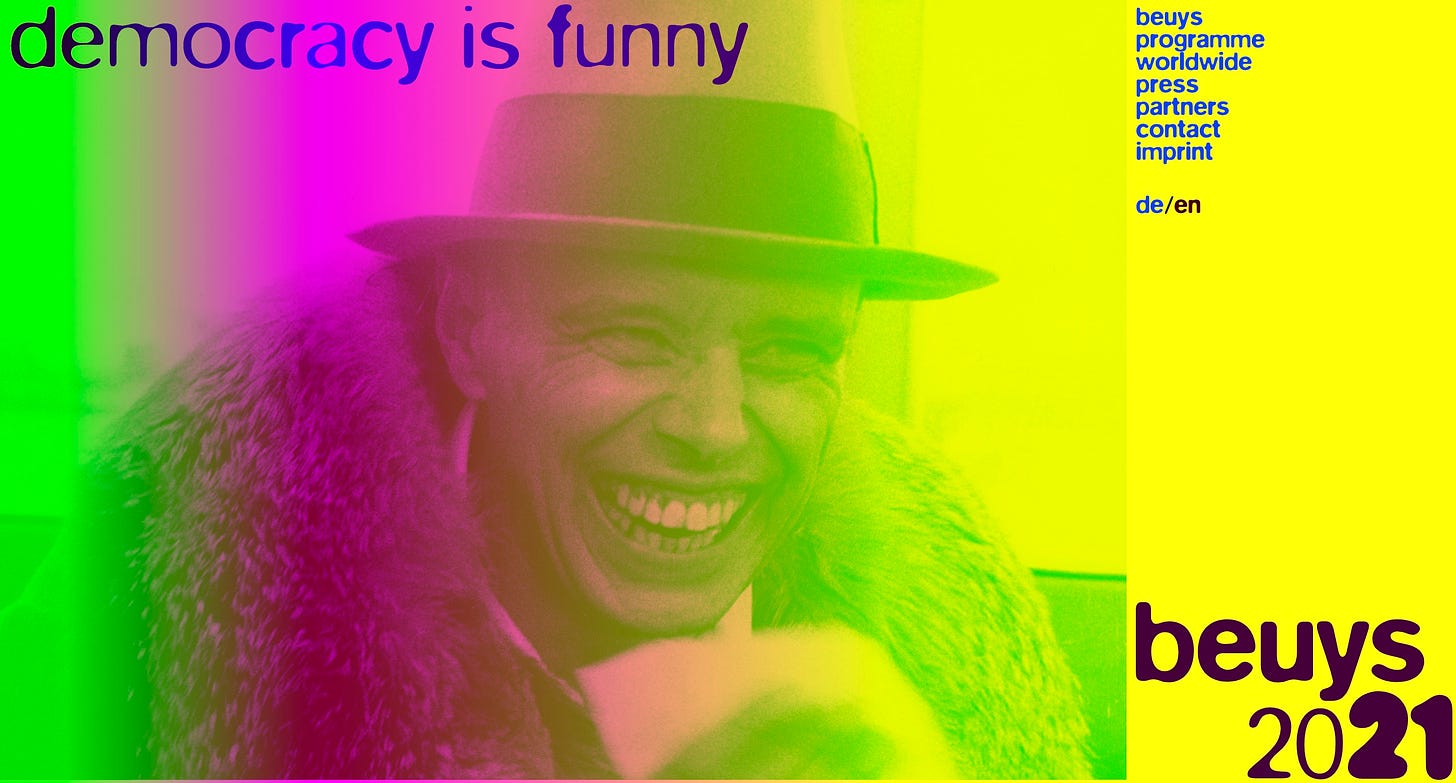

You might have heard that Beuys was shot down in his Stuka plane over Crimea, to be rescued by Tartars who wrapped his body in fat and felt to keep him warm (much like Han Solo did with Luke Skywalker on the ice planet). Only problems: the plane wasn’t shot down. Instead, it crash landed in bad weather, in all likelihood because of the pilot’s inexperience (and possibly because the navigator, a certain Joseph Beuys, did a terrible job; interesting detail: Beuys never became a pilot because in all likelihood he was colourblind.). Also: There was no snow that year (oops). The pilot died, but Beuys survived with minor injuries and had a short stint in a German field hospital (there is at least one witness, a German officer). At that stage, there also were no tartars roaming Crimea (this would have cost them their lives under German occupation). So there were no fat or felt (in all likelihood, the fat connection is provided by the fact that Beuys’ hometown featured a very large margarine factory). And Beuys wearing that hat because of the metal plate in his head? Lolz. There was no metal plate. He simple started wearing a hat when his hair started thinning.

Oh, and Beuys then went to Stuka personnel reunions in the 1970s (this article has a picture from such an event), and he never saw anything wrong with that. Just like what you’d imagine someone do who just a little later joined the nascent German Green Party one of whose main political topics at the time was the anti-nuclear peace movement. Stuka personnel for peace — some idea, huh?

It just keeps going and going and going. Beuys grew up under the Nazis and actually didn’t see all that much wrong with them, even later. He also became completely enthralled with a certain Rudolf Steiner, whom you might know as the person behind Waldorf Schools. Turns out Steiner was also a “philosopher,” with many of his ideas… how can I say this? Maybe this way: completely fucking insane.

And I’m only a third of the way through the book. Holy mackerel! In case you’re wondering: Riegel not only details all of that, he also has receipts. It’s all meticulously researched. Some of Beuys’ myths had already been debunked, but the scope of Riegel’s debunking is a completely different level.

Twenty twenty one is the Stuka navigator’s centenary year in Germany. Democracy is funny indeed (this is an actual cropped screenshot).

That’s it for today. If you are having to live in the Northern hemisphere, you’re probably as fed up with the winter as I am. I’m now at the point where I’m not even trying any longer to make the best of it. I suppose I have reached the final stage of the grieving process (I didn’t come up with this idea — see it here).

I also just had another birthday. While I usually don’t care all that much about my birthdays, this time it was personal. Something really got to me. I’ll get over it (I hope), but it might take a few more days.

So I hope you’re doing better than I’m doing right now: I hope you’re safe and well.

As always thank you for reading!

— Jörg